2.1 Salvage

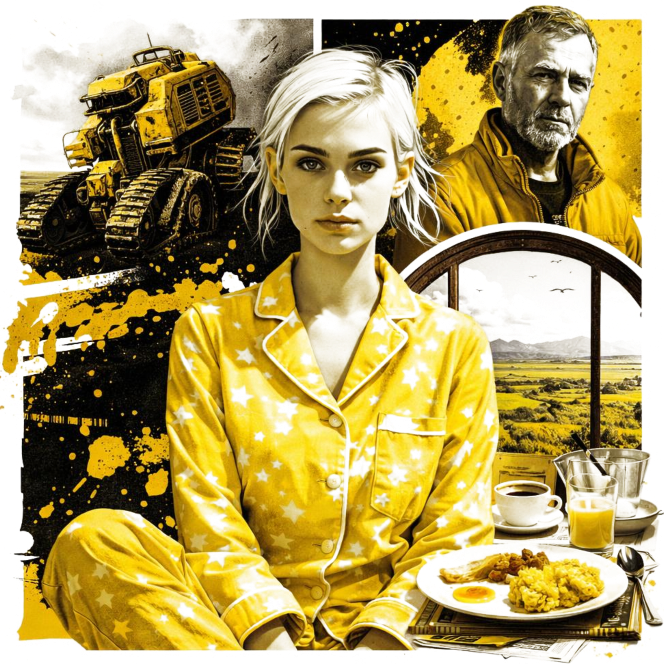

Breakfast smells like burnt protein paste. Sylvia has attempted what she calls ‘heritage pancakes,’ which involves taking perfectly good, reconstituted grain flour and doing something regrettable to it with a heated pan. The pancakes are stacked on a plate in the centre of the kitchen table, arranged with the kind of deliberate care that says, ‘I’m trying very hard and you will appreciate it. The pancakes are not quite round. They’re not quite flat. And they’re the colour of things that have been in contact with excessive heat for too long.

Jo’s father, David, is studying them. He’s wearing his work clothes already, even though it’s barely seven in the morning: canvas trousers held up with suspenders, a shirt that was blue once but has been washed into a colour that doesn’t have a name, and boots that definitely sees mud more than it sees soap.

“These pancakes look almost edible,” he says, which is the kind of lie you tell when you’ve been married for six years.

Sylvia beams. “That’s just what I was aiming for,” she says.

Sylvia is Jo’s stepmother. Not that anybody uses that term anymore. It sounds like something out of a pre-Restoration fairy tale. Sylvia arrived when Jo was seventeen, fresh from the Central Administrative Sector with administrative qualifications and a genuine desire to contribute to agricultural life. She had lasted three weeks before realising that farming involved more physical labour and less administrative policy than she had anticipated, but by then she had already married David and it would have been a nightmare to leave. Breaking a newly signed partnership requires council mediation, financial settlements, and the kind of bureaucratic scrutiny that makes everyone involved wish they had thought harder before signing. The Restoration had streamlined many things, but ending marriages wasn’t one of them. Partly because stable partnerships were considered essential to community cohesion, and partly because the World Stewardship Council believed that making divorce difficult would encourage people to choose more carefully in the first place.

Cass is at the counter, arranging fresh-cut fruit on a serving plate. She’s nineteen but carries herself with the assurance of someone much older. Her dark hair is pulled back in a practical braid, and she’s already dressed in the khaki field trousers and sensible boots that are her uniform even on college days. Her last week of the semester starts tomorrow. She’ll come back from university and slot perfectly into farm life, probably with innovative ideas about yield optimisation and sustainable practices.

“I used real sugar,” Sylvia announces, as if this explains everything. “The kind they make from beets, not the synthetic stuff. I thought, it’s Jo’s birthday so, we should do something special.”

Jo smiles. Her birthday was yesterday. They’re celebrating this morning because yesterday, and the day before that, Jo had been in New Helion drinking Meridian Sunsets and contemplating pilots and escape routes. She had told her father she was going to visit Mira. This was technically true, just incomplete. But you don’t tell your farmer father that you spent your twenty-third birthday planning to abandon the paradise he’s spent his life maintaining. That’s the kind of conversation that requires more courage than she currently possesses.

“Thank you,” Jo says, taking three pancakes. They’re heavier than they should be. Maybe gravity affects Sylvia’s cooking differently than it affects normal food. She pours something that’s labelled ‘maple-inspired syrup’ over them, and watches it pool in the crater-like indentations.

David takes two pancakes, adds syrup, and cuts into them with his fork. He chews thoughtfully. “Definitely special,” he says.

They eat in companionable silence for a moment. The kitchen window looks out over the eastern fields where heritage wheat is doing what heritage wheat does: growing at historically accurate rates in soil that’s been restored to pre-industrial nutrient levels. Beyond the wheat, Jo can see the old barn where they keep the equipment and beyond that, the processing facility where the harvest waits to be sorted, cleaned, and shipped to wherever the Agricultural Distribution Council decides where the heritage wheat should go. Some of it will stay on Earth, feeding the consolidated cities and agricultural communities. But some of it will be loaded onto cargo ships and sent to the colonies, where people who had the good fortune to leave before the gates closed will turn it into bread and pasta and all the ordinary things that require wheat. Jo has spent considerable time being jealous of grain. Wheat gets to leave. Wheat gets loaded onto ships without needing special skills or council approval or family connections. Wheat just has to exist and be useful, and that’s enough. Meanwhile Jo, who is arguably more complex and certainly more motivated than wheat, has to stay put and watch it go. It’s the same view she’s had her entire life. Twenty-three years of mornings, looking out this window at various stages of crop rotation, watching her crops achieve the freedom she can’t.

“We need to look at the harvester after breakfast,” David says. He doesn’t need to specify which harvester. They have three of them. The farm is big. When David says, ‘the harvester,’ there’s only one machine he could mean. Harvester Two, officially designated H2-Agricultural-Eastern-Sector-447, unofficially known as ‘that temperamental bastard.’

This is not unexpected. They always have problems with the harvester. Harvester One runs smoothly. Harvester Three is newer, less finicky, blessed with post-update engineering that actually solved problems instead of creating them. But Harvester Two is a Consolidation-era machine built during that optimistic period when the World Stewardship Council believed everything could be standardised, centralised, and made foolproof.

“Which problem?” Jo asks. “The calibration issue or the hydraulic leak or the sensor malfunction or is it the thing where it decides wheat isn’t wheat and refuses to harvest?”

“It’s a new problem,” her father says. “The drive system’s making a sound like it’s trying to communicate with us. It’s a mechanical language I don’t speak. I’m guessing it’s the coupling mechanism.” He pauses to attempt another bite of pancake. “We can probably limp through this week’s work if we’re careful, but we’ll need parts soon. Real parts, not the refurbished ones that last three weeks and then fail.”

Sylvia looks worried. This is her default expression when farming equipment is mentioned. It’s as if she suspects all machines are plotting against humanity. “Surely we can order parts from the distribution centre?”

“Yes, we can order them,” David says. “Whether they’ll arrive in time is another question. The distribution centre’s backlogged. Apparently, they call it ‘supply chain optimisation,’ which as far as I can tell means they’re optimising the supply right out of the chain.” He pushes his plate away, pancakes half-finished. This is significant. David never wastes food.

“Or,” Cass says from the counter, not looking up from her fruit arrangement, “we could just sell to Baine Joyce and be done with it. He called again yesterday. Third time this month.”

David’s jaw tightens. “We’re not selling to Joyce.”

Jo knows about Baine Joyce. Everyone in the Agricultural Sector knows about Baine Joyce. He’s in his late fifties, still trading on a reputation built during the Restoration when he’d been a minor logistics coordinator who’d somehow parlayed that position into considerable wealth and influence. These days he acquires ‘underperforming’ farms, consolidates them into larger operations, and manages them through hired administrators. He’s been circling their farm ever since their mother died and left David running the operation alone. Joyce’s offers started polite. They’ve become increasingly insistent.

“He said if we don’t respond to his latest offer, he’ll assume we’re not serious about maintaining the property,” Cass continues, finally turning to face the table. “I’m just saying, maybe we should at least hear what he’s proposing. With what he’s offering, we could buy land in the Southern Margins. Three times the acreage for half the cost. The soil’s still recovering, sure, but that’s exactly the kind of challenge I’ve been training for. We could build something really significant there.”

“We’re not hearing anything from that scavenger,” David says flatly. “This farm has been in our family for three generations. We’re not handing it over to some Restoration profiteer who thinks land is just another asset to optimise.” He meets Cass’s gaze. “Besides, didn’t you tell me last week you wanted to implement those new soil management protocols you’re learning about? Can’t do that if we sell to Joyce.”

Cass smiles. She brings the fruit plate to the table. As she sets it down, she glances at Jo. “Marcus stopped by yesterday while you were in New Helion. He helped Dad with the irrigation system in the west field. Said to tell you he’d try to come by later this week.” There’s something in Cass’s tone. Not quite a longing, but close.

“That’s thoughtful of him,” Jo says carefully. Her sister wants to farm, she wants a future that looks exactly like the past. And somewhere in that future, Jo suspects, Cass has made space for Marcus. If only Jo would step aside.

“Anyway,” David continues, clearly eager to change the subject, “I might swing by that scrapyard over in Tanners’ Ravine. See if Todd Greten’s got anything that’ll fit our particular model of disaster.”

Jo’s fork stops halfway to her mouth. Tanners’ Ravine. The scrapyard. The one Petra mentioned. The one she’d decided last night she needs to visit. The one with parts from old ships and probably also with parts from old harvesters because scrapyards don’t specialise. They accumulate.

“Tanners’ Ravine?” Jo keeps her voice carefully neutral. “That’s hours away.”

“Two and a half if you take the old service road,” her father says. “Though calling it a road is generous.” He stands, carries his plate to the cleaning unit. “I was thinking of going this morning. If you want to come along. Might be educational. Todd’s got stories about the exodus years that’ll make you appreciate how much better we have it now.”

Educational. That’s exactly what Jo needs: an education in salvage, in what’s available, in what she might be able to purchase or barter for when nobody’s looking. Her heart begins doing something complicated in her chest, an excited rhythm that doesn’t match normal circulation. This is luck. This is the universe deciding to cooperate with her improbable plans. This is an opportunity arriving precisely when she needs it, which makes her slightly suspicious because opportunities usually don’t work that way.

Or maybe they do. Rural Earth people often think of the universe as something close to what God used to be in the old religions, before the Restoration made faith seem unnecessary. It’s not an omnipotent deity exactly, but something attentive and personal. Something that notices when you need help and sometimes, if you’ve been paying attention to the soil and the seasons and the small kindnesses that hold communities together, sends you what you need. City people call it superstition, this lingering sense that the universe has opinions about your life. But farmers know better. The universe does have patterns. It has rhythms. And if you work with those rhythms rather than against them, sometimes things align in ways that look like intervention but are really just cooperation. Jo’s not sure she believes in universal providence. But she’s also learnt not to question good timing when it appears.

“I’ll come,” Jo says, trying not to sound too eager. “I mean, if you need help loading parts or whatever.”

“I always need help loading parts,” her father says. He’s rinsing his plate now, watching water run over Sylvia’s pancake remnants. “Todd’s got a forklift but it’s older than the harvester and about as reliable. Last time I was there he was using a dangerous looking pulley system made from ship cable.”

Sylvia’s clearing the table. She appears a little more cheerful suggesting she’s relieved breakfast is almost over. “What time will you be back?” she asks David. This is her way of planning, of imposing structure on the chaos of farm life. She likes to know when meals will happen, who will attend them, whether she needs to attempt cooking or if they can safely rely on the automated systems.

“I’ll be back in time for tea,” David says. “Unless Todd gets talking about the time he worked on the colony ships and decides I need to hear the entire history of time-bending propulsion systems again. That man can talk about engine configurations like some people talk about religion.” He glances at Jo. “Actually, you coming along might work out well. Todd likes an audience for his stories. You can keep him occupied while I dig through the parts inventory. He’s more likely to remember where he’s stashed things if he’s got someone listening to his adventures. Especially someone pretty.”

Time-bending propulsion systems. Colony ships. The scrapyard isn’t just a collection of broken farm equipment and spare parts. It’s a museum of exodus-era technology. It’s a library of how people used to leave Earth when leaving was still possible, still permitted, still a dream you could actually pursue instead of just fantasise about while pretending to check irrigation schedules.

“I’d like to come,” Jo says again, and this time she lets a little of her eagerness show. Let her father think she’s interested in learning about equipment maintenance, about agricultural logistics, about the practical skills that keep farms running. Let him think whatever he needs to think. Today, she’ll see the scrapyard. Today, she’ll start counting parts for a ship instead of just dreaming about them.

The thought should be thrilling. Instead, Jo feels a small knot of something that might be fear or might be realism tightening in her chest. She knows about harvesters. She knows about irrigation systems and soil pH and the seventeen different ways heritage wheat can fail to thrive. She knows how to rebuild a tractor engine and troubleshoot sensor malfunctions and coax temperamental machinery into cooperating for just one more season. But a spaceship? A ship capable of atmospheric exit, of navigating the void, of surviving a bend in time where physics itself becomes negotiable and a journey of decades compresses into subjective minutes? That’s not farm equipment scaled up. That’s an entirely different species of engineering.

She’s been preparing, in her way. Late nights in her room, reading engineering documents she’s accessed through the agricultural library network. She’s read technical manuals that were supposed to be restricted but weren’t restricted enough, especially if you know how to route your requests through research channels. Propulsion theory. Life support systems. Hull integrity under pressure differentials. Time-bending mechanics that made her head hurt but that she read anyway, paragraph by painful paragraph, trying to understand how humans had managed to cheat relativity and turn century-long voyages into survivable trips. She’s learnt enough to know how much she doesn’t know. She’s learnt enough to understand that the gap between ‘has read about’ and ‘can actually build’ is vast enough to swallow entire dreams whole.

But now the dream has come knocking on her door wearing her father’s work boots and offering her a ride to Todd Greten’s scrapyard. And facing the actual possibility, makes her realise just how monumental this is. How impossible. How completely insane it is to think that a twenty-three-year-old farmer with some smuggled engineering texts and a talent for fixing farm machinery could somehow assemble a functional spacecraft from salvage. The universe might cooperate with your rhythms, but it doesn’t suspend the laws of physics just because you’re determined.

She takes another bite of Sylvia’s pancake. It’s terrible, heavy, burnt, and far too sweet. But she eats it anyway, and smiles, and thinks about Tanners’ Ravine and ship cables and the sound of a harvester trying to communicate in a mechanical language.

After breakfast, Jo heads upstairs to change. Her father’s already outside checking the truck’s charge levels, which gives her a few minutes.

Her bedroom is small but it’s hers in a way nothing else on the farm is. The walls are covered with images she’s collected over the years. There’s a massive photograph of the Kepler Station hanging over her bed, all spinning rings and solar arrays catching starlight. Next to it, a smaller image of New Mars at sunset, the terraformed landscape painted in colours Earth hasn’t seen in generations. Three colony ships in various stages of departure, their hulls catching light as they climb away from gravity. And there, in the corner where she can see it from her pillow every night: Captain Ines Okafor at the helm of the Meridian, the woman who’d led the third wave colony ship and then gone back for two more runs before the exodus ended. She’s grinning in the photo, one hand on the control panel, her flight jacket worn to soft leather, her hair in locks that float slightly in the reduced gravity. Jo’s had that picture for six years. She’s pretty sure half her determination to leave comes from wanting to be someone like Okafor.

Her desk is a chaos of crop reports with technical diagrams hidden between the pages. Hull stress calculations tucked inside fertiliser schedules. Propulsion theory disguised as irrigation data. She’s gotten good at hiding what she’s really studying.

And in the corner by the window, Pru’s docking station: a modified charging unit Jo built from spare parts, with a mounting bracket that holds the robot’s body upright. The body itself is humanoid but scaled down. Pru is a meter tall with scratched white polymer casing that’s been patched in several places with whatever Jo could find. One leg is slightly shorter than the other, which creates the limp. That’s from a mismatched replacement part Jo had installed when the original leg actuator failed. She could probably fix it properly, but there’s something endearing about Pru’s uneven gait, something that makes the robot feel more like a companion than a surveillance device.

Jo pulls off her pyjamas. She pauses for a moment to look at herself in the mirror. All one-metre-seventy of her soft, naked flesh. “How far are you willing to go to get off this planet?” she asks her reflection. She reaches for her work clothes. Canvas trousers, a shirt that used to be her father’s, thick socks that can handle a day of walking through mud and scrap metal. She pulls the core module from her jacket pocket and crosses to Pru’s station.

The module slots into the housing on Pru’s back with a satisfying click. There’s a brief whir as systems come online, then Pru’s optical sensors light up – two blue lights that give the impression of eyes even though they’re really just status indicators.

“Good morning, Jo,” Pru says. The body straightens as systems run through their startup diagnostics. The left leg adjusts with a slight grinding sound. “I have seventeen notifications regarding your departure timeline calculations from last night. Would you like to review them?”

“Not now,” Jo says, sitting on her bed to pull on her boots. “We’re going to Tanners’ Ravine. The scrapyard.”

Pru’s head tilts. Jo programmed this gesture during one of her modification sessions. The movement is smooth but deliberate, almost curious. “Tanners’ Ravine. Location of Todd Greten’s salvage operation. Estimated inventory includes: agricultural equipment, residential hardware, and…” There’s a pause. “And approximately forty-seven tonnes of exodus-era spacecraft components according to regional salvage databases last updated four years ago.”

Jo stops mid-lace. “Forty-seven tonnes? That’s specific.”

“I accessed historical manifests during your research sessions. Cross-referenced with decommissioned vessel registrations and likely salvage acquisition patterns. Would you like me to compile a prioritised acquisition list based on your propulsion system sketches and available currency reserves?”

“You can do that?”

“My adult female behaviour protocols include budget management and resource allocation planning. I have felt it necessary to repurpose these protocols for spacecraft construction. Although this is not their intended application.”

Jo smiles. “That’s the best misuse of programming I’ve ever heard. Yes. Make the list. But Pru…”

“Yes?”

“You’re coming with me. Dad’s assistant broke down last month and he hasn’t replaced it yet. If he asks, you’ll be helpful with calculations and inventory.”

Pru’s head tilts the other direction. One hand raises slightly. This is another gesture Jo had added. “An excellent cover story. Particularly since your father’s Model 63 Agricultural Assistant did experience catastrophic motor failure and your father declined the council’s replacement offer citing budget constraints.”

“You knew about that?”

“I monitor all household equipment status reports. It’s part of my responsible adult female behaviour protocols. I must anticipate domestic needs.” There’s a pause. “Also, accompanying you to the scrapyard increases my ability to provide real-time assessment of available components. Current project timeline still estimates four point three years to completion, assuming optimal component acquisition and minimal regulatory interference. My presence may reduce that estimate.”

“Four point three years,” Jo repeats. It sounds both impossibly long and impossibly short. Four more years of wheat and Marcus and broken harvesters. Four years of counting sunrises over the same fields. But also: four years until she could leave. Four years until she might watch a sunrise from somewhere else entirely. Four years until maybe she could be standing on a colony ship’s bridge like Okafor, grinning at the controls, going somewhere that mattered.

“Probability of success has increased to fourteen percent,” Pru adds helpfully. “Your father’s offer to visit the scrapyard represents a seven percent improvement in resource access likelihood. My direct assessment of inventory could add another three to five percent.”

“Only fourteen percent?”

“I am programmed for realistic assessment. Would you prefer I inflate the probability to support your emotional state? Many personal development assistants include motivational encouragement features.”

“No,” Jo says, standing and checking herself in the mirror. She looks like a farmer. She looks like someone who belongs here. That’s good. That’s the disguise she needs. “Keep it realistic. I’d rather know the actual odds.”

Jo lifts Pru from the docking station. The robot’s weight is familiar in her arms. Eight kilograms of hardware and modified programming. Pru’s legs dangle, the shorter one swinging slightly. “Just remember: in front of Dad, you’re a helpful assistant calculating part specifications. Not a co-conspirator in illegal spacecraft construction.”

“Understood. I will maintain behavioural protocols.”

Jo heads for the door, Pru cradled in one arm, and glances back at her room – at Okafor’s grin, at the Kepler Station’s impossible grace, at the empty docking station that looks suddenly lonely without its resident. “Fourteen percent,” she says. “That’s better than yesterday.”

Downstairs, her father is waiting by the door with his work jacket and a thermos. He sees Pru in Jo’s arms and nods approvingly. “Good thinking. Is that unit still working?”

“Better than your assistant,” Jo says.